An alternative working title for this note was “management teams behaving badly”, but we felt it more apt to invoke the Hippocratic oath, the cornerstone of medicine that emphasises the importance of avoiding harm to patients above all else. If we consider the ‘patients’ in this context as public companies, management teams across Australia would do well to consider their own Hippocratic oath to shareholders: first, don’t do anything dumb. This should go without saying, and yet these past 12 months feel littered with the fallout of dumb decisions from management teams, primarily regarding the pursuit of large-scale M&A.

Is this a bit too harsh? Let’s examine the evidence.

- Orora’s value-destructive $2.2bn acquisition of Saverglass, which managed the cardinal sin and hat trick of gearing up the balance sheet to purchase a business off private equity in a new jurisdiction (France – not renowned for its business-friendly labour laws). Orora’s share price touched $3.75 in the week before the deal announcement, and today languishes below $2;

- Viva’s $1.15bn acquisition of On The Run, which was touted to add $165m in EBITDA post synergies, for an acquisition multiple of 7x EV/EBITDA, yet contributed $45m in FY24 – a true price of 26x EV/EBITDA. The deal also allowed the founders to strip out the property, saddling Viva with an $80m a year lease cost;

- CSL’s acquisition of Vifor, which has so far proven a dud, torching the group’s historically high ROIC >20% down to a paltry 12%;

- Healius’s $300m acquisition of Agilex Biolabs, promising EBITDA of $16m and delivering a paltry $4m in its first year of ownership, prompting Healius to achieve the impressive feat of exiting the covid-era pathology funding avalanche with a balance sheet issue requiring an emergency capital raise;

- Perpetual’s disastrous $2bn acquisition of Pendal;

- Ramsay’s $1.4bn acquisition of Elysium in 2022, which they funded entirely through debt. To date, the business generates barely any profit.

The most topical current example of a management team violating the Hippocratic oath to shareholders has to be James Hardie’s proposed $8.75bn1 acquisition of Azek, which we will return to later on in this piece.

All of this begs the question as to why. Why does large-scale M&A typically destroy value? The answer is because of its deleterious impact on the returns of the acquirer’s business. Over the long term, a company’s share price will follow the return on capital it generates. The issue with large-scale M&A is that it typically enshrines a low return on capital from day one, as the acquirer must pay a takeover premium to “win” the target.

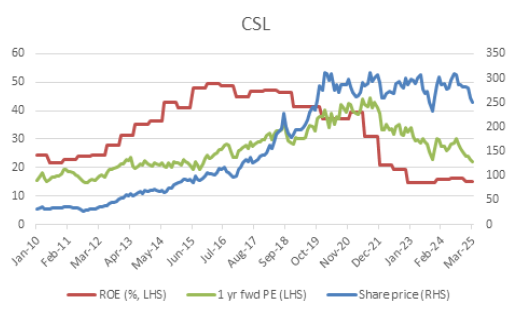

Picking on CSL as an example, much has been made of the extraordinary de-rate in CSL shares over the last five years as the share price has gone nowhere. However, when viewed through the lens of the returns the company generates, the derate makes a lot more sense.

Source: FactSet, Airlie Research

CSL enjoyed a phenomenal run-up in its share price over the decade 2010-2020, as improving return on equity (from 24% in 2010 to a peak of 47% in 2018) drove a PE re-rate from 15x to a peak of 45x earnings. ROE has since declined to 15%, primarily due to the combination of covid-era donor fee inflation shredding CSL’s plasma business gross margin, and the acquisition of Vifor, which we estimate generates a ROIC of c3% on the initial A$17.2bn invested. Hence, the derate CSL has experienced makes sense in the context of some external misfortune and some capital allocation own goals. The good news, and why we own CSL in the fund today, is that we believe incremental returns should improve from here, as gross margins improve in Behring and the company shows more discipline on capex. The value destruction from the acquisition of Vifor is a one-and-done phenomenon, which is why we are so focused on avoiding harm (dumb acquisitions) in the first place, as we believe the CSL share price would be much higher today if they had not done this deal.

Applying this framework to the Hardie acquisition of Azek highlights the likely immediate value destruction of the deal, one that tarnishes Hardie’s reputation as one of the cleanest, high-returning organic growth stories listed on the ASX. Consensus estimates have James Hardie generating EBIT of $865m for FY25, from an invested capital base of just $2.8bn, for a pre-tax return on invested capital of 32%. This is an extraordinarily high return for a manufacturing business. The $2.8bn of invested capital mostly represents the sum of the capital invested over several decades in building up the company’s largest division, North American Fibre Cement, comprising 19 manufacturing plants globally, three R&D centres, the working capital tied up in the channel, and the historic goodwill associated with the acquisition of Fermacell. With the proposed US$8.75bn acquisition of Azek, a new(ish) management team (CEO Aaron Erter was appointed only twoand-a-half years ago) has seen fit to add an extraordinary $8.75bn to the existing capital base of Hardie’ - a 312% increase in the company’s invested capital base overnight.

Consensus forecasts have Azek earning US$270m EBIT in FY25. This would imply a day one pre-tax return on invested capital of 3% for James Hardie shareholders. For Azek to generate an acceptable return for shareholders of, say, 10-12% pre-tax, you would have to believe Azek can earn a sustainable EBIT of US$875m-1bn; that is, a trebling of the current forecast EBIT. This seems highly unlikely. If we take the earnings base of US$270m and give management the benefit of the doubt on all outlined cost synergies of US$125m, this is a $395m EBIT base. For the business to generate an acceptable return of 10-12% pre-tax, Hardie’s would have had to have paid US$3.3bn-$4bn for Azek; that is, the deal looks immediately value destructive to the tune of US$4.5-5bn. Now obviously if management can achieve the outlined $500m in revenue synergies from the deal, this will offset some or all of this value destruction. However, that will be proven out over the medium to long term. Incidentally, two weeks before the deal was announced James Hardie had a market cap of US$14bn, which has fallen to cUS$10bn today – indicating the market has been quick to price in this value destruction.

Now the bigger question is where to from here – the value destruction of this deal has been spotted by an efficient market very quickly. The extent to which James Hardie “makes good” on this deal (from the new, lower share price starting point) will come down to execution. Azek is by no means a bad business, and there appears to be logic to putting these products together under one manufacturer when selling into the same US R&R channel. As with any acquisition, the long-term success will be a function of the extent to which one plus one equals something more than two. However, when you pay up to begin with, one plus one must equal something more than three for value to eventually accrue to James Hardie shareholders.

Markets are efficient, no doubt, which is why we ask (beg?) Australian management teams to adhere to the Hippocratic oath when considering M&A: first, don’t do anything dumb. And we’d take it so far to suggest that most large deals, no matter what the bankers cook up regarding synergies, EPS accretion, multiple re-rates, etc., are simply dumb deals for acquirers – an immediate value transfer to target shareholders that will sit on returns and immediately torch value.

By Emma Fisher, Deputy Head of Australian Equities & Portfolio Manager

1 US$8.75bn refers to the value of the deal on the day of announcement. James Hardie’s share price has since fallen, hence the scrip component and overall deal value will be lower.